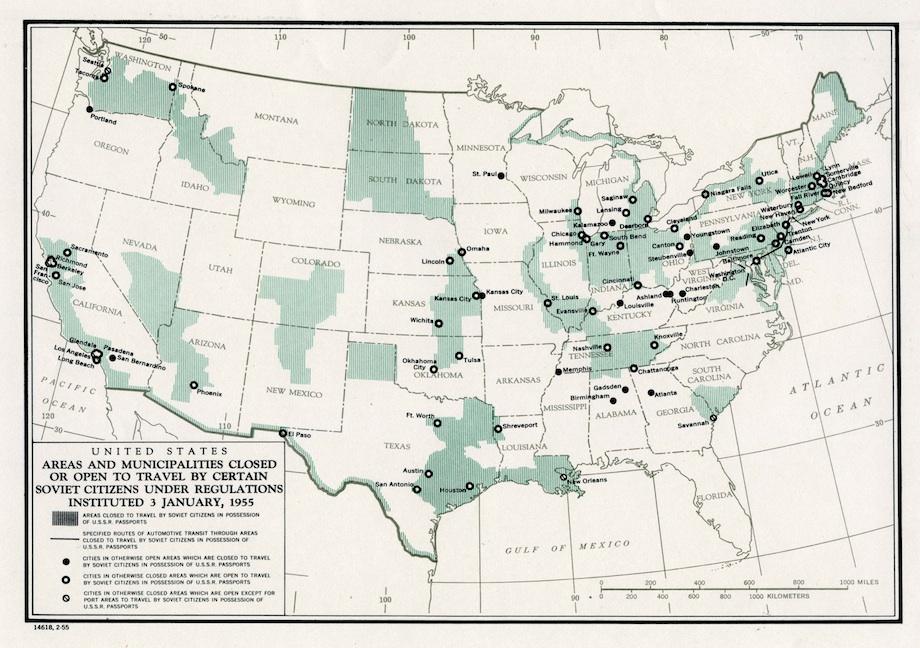

This map shows where Soviet citizens, who were required to have a detailed itinerary approved before obtaining a visa, could and could not go during their time in the United States. Most ports, coastlines, and weapons facilities were off-limits, as were industrial centers and several cities in the Jim Crow South.

These restrictions mirrored Soviet constraints on American travel to the USSR. Both the United States and the Soviet Union had closely controlled the movement of all foreign visitors since World War II. A 1952 law in the U.S. barred the admission of all Communists, and therefore of Soviet citizens.

The Soviets’ decision to relax their controls after Joseph Stalin’s death in March 1953 left the U.S. open to charges that it, not the USSR, was operating behind an Iron Curtain. President Eisenhower and his foreign policy advisers decided to mimic Soviet policy as closely as possible: As of early 1955, citizens of either nation could enter approximately 70 percent of the other’s territory, including 70 percent of cities with populations greater than 100,000.

Travel restrictions on Soviet private citizens stayed in place, enforced by the Departments of State and Justice, until the Kennedy administration unilaterally lifted them in 1962 as a symbol of the openness of American society. Controls on visits from journalists and government officials, by contrast, lingered until the end of the Cold War. As the recent story of the American diplomat arrested in Moscow on charges of CIA recruitment activities suggests, the history of mutual suspicion still occasionally surfaces.