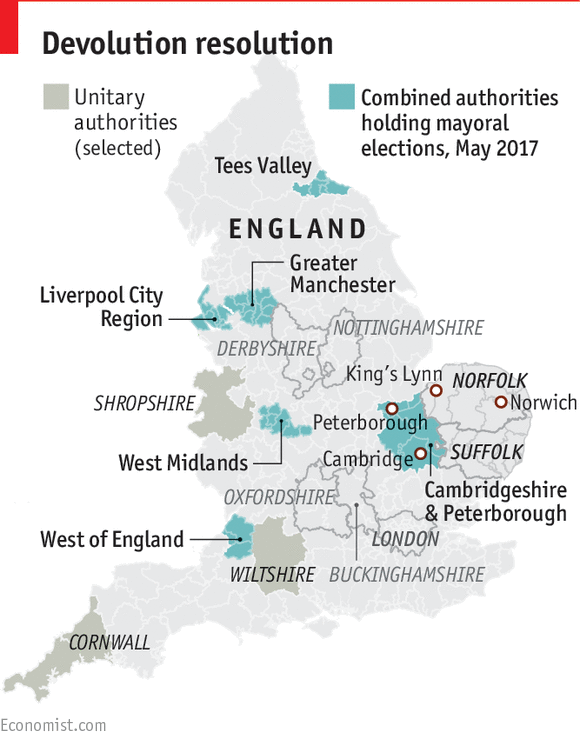

In May, Liverpool, Greater Manchester and four other combined authorities (see map) will elect a metro mayor for the first time. They are the poster children of the “devolution revolution” launched by the then chancellor, George Osborne, in 2015. The hope was that more joined-up decision-making at local level would boost regional economies and raise productivity. But many rural areas did not even submit a devolution proposal. Elsewhere local councillors rejected the notion. There are fears that, beyond the six deals concluded, it will be hard to do more. Lord Porter, head of the Local Government Association, said last month that he believes “devolution is dead.”

Some counties are restructuring anyway. Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire each plan to abolish their county, district and city councils and form a “unitary” one. Cornwall, Wiltshire and Shropshire have already done so. But district councils often align with parliamentary constituencies and, as district councillors act as ground troops in general elections, many MPs do not want unitaries.

The biggest problem is persuading the people in places like King’s Lynn to support change. “If you asked all my friends in the town,” says one lifelong resident out shopping with his wife, “I doubt any of them have even heard of devolution.”